Antumbra

2024

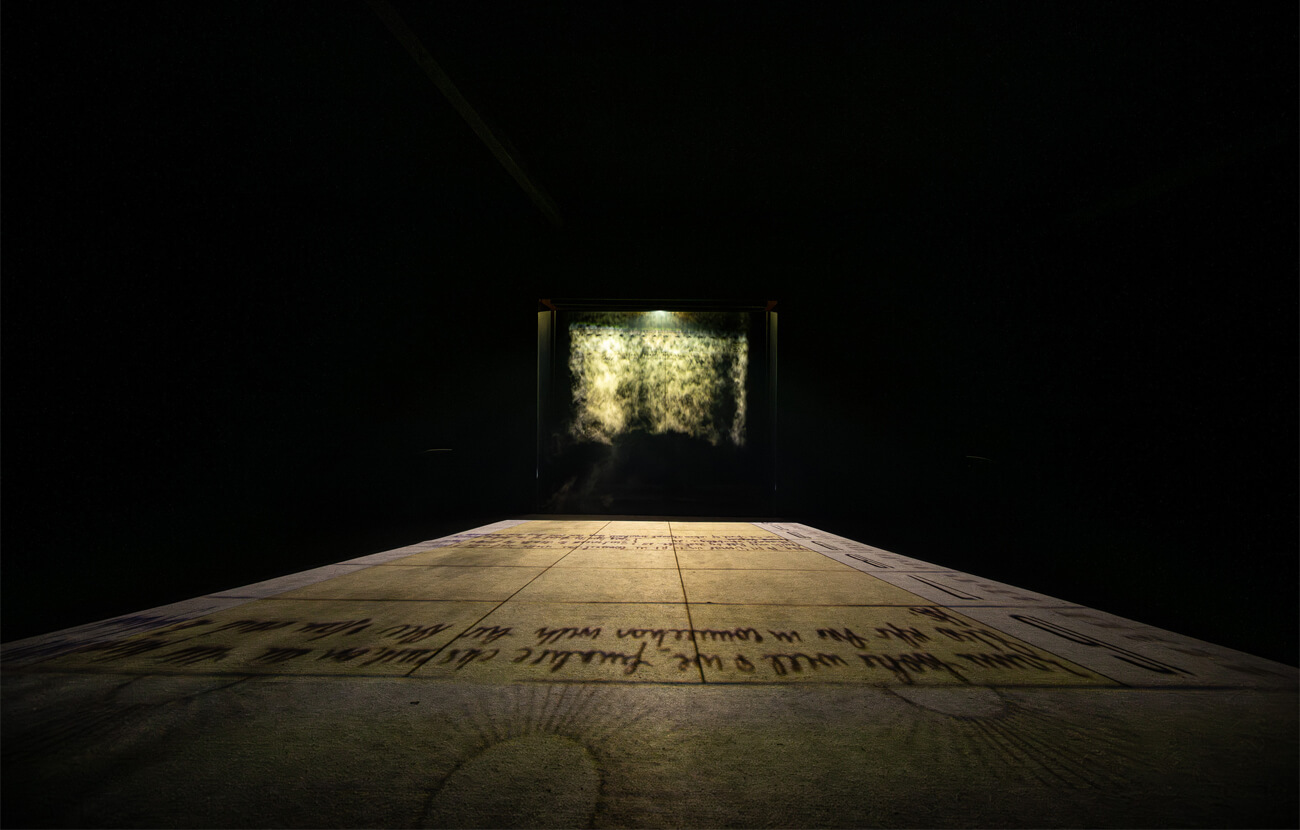

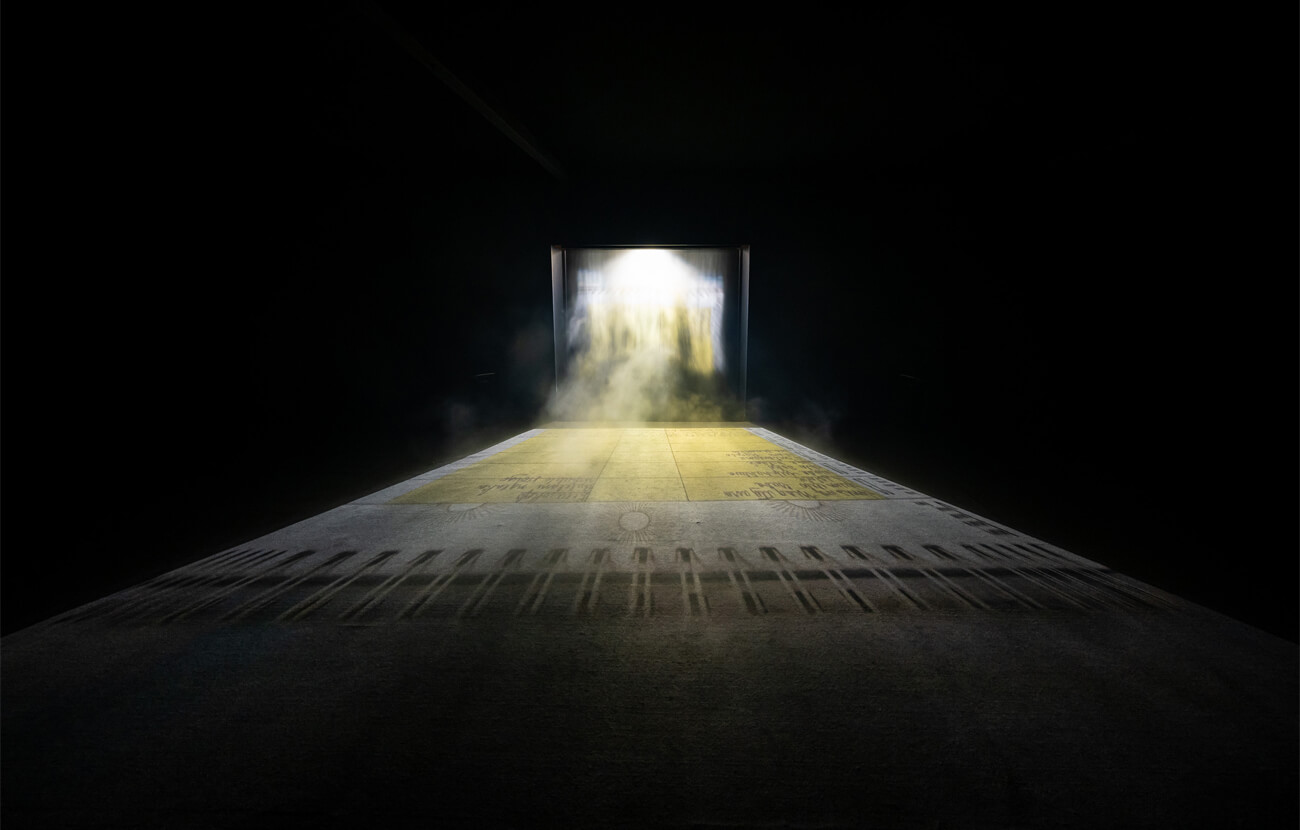

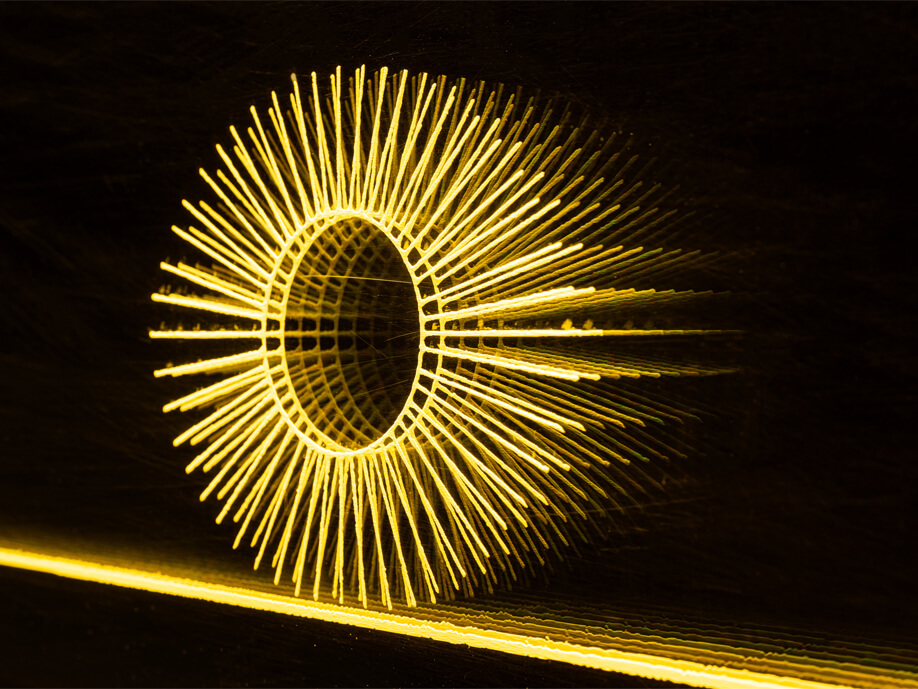

fogscreen projection, backlit translite, video on monitior, infinity mirror

display dimensions variable

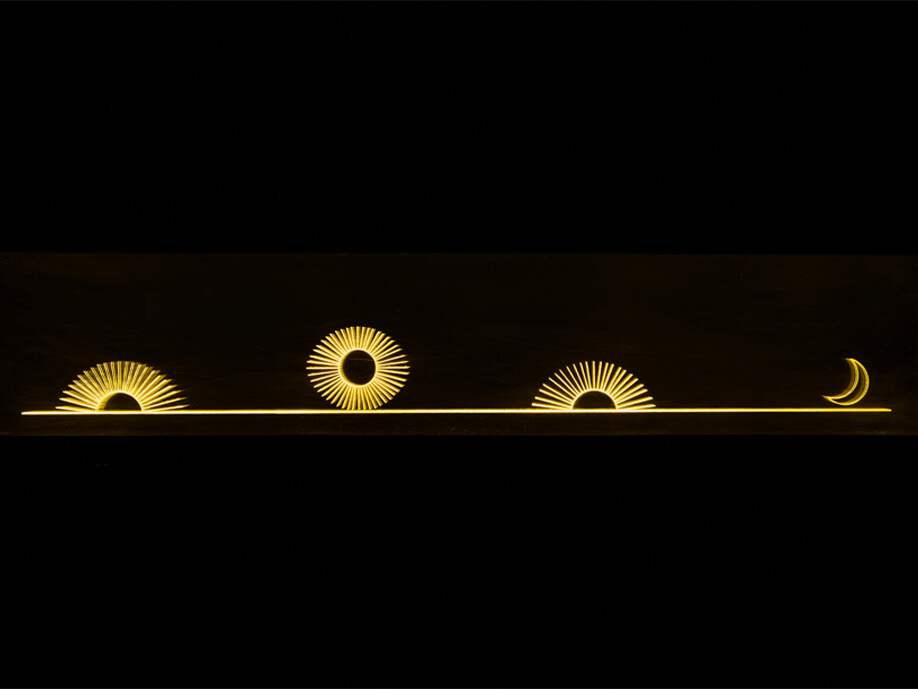

Jitish Kallat’s immersive installation Antumbra (2024) is a reflection on the passage of time, interwoven with themes of confinement, occlusion, resilience, and hope. This work follows Kallat’s Public Notice trilogy (2002–2010) and Covering Letter (2012), where a historical utterance or document serves as a site for deliberation. A recurring element in Kallat’s work is the incorporation of dates, measurements, and numbers as ordering and sense-making devices.

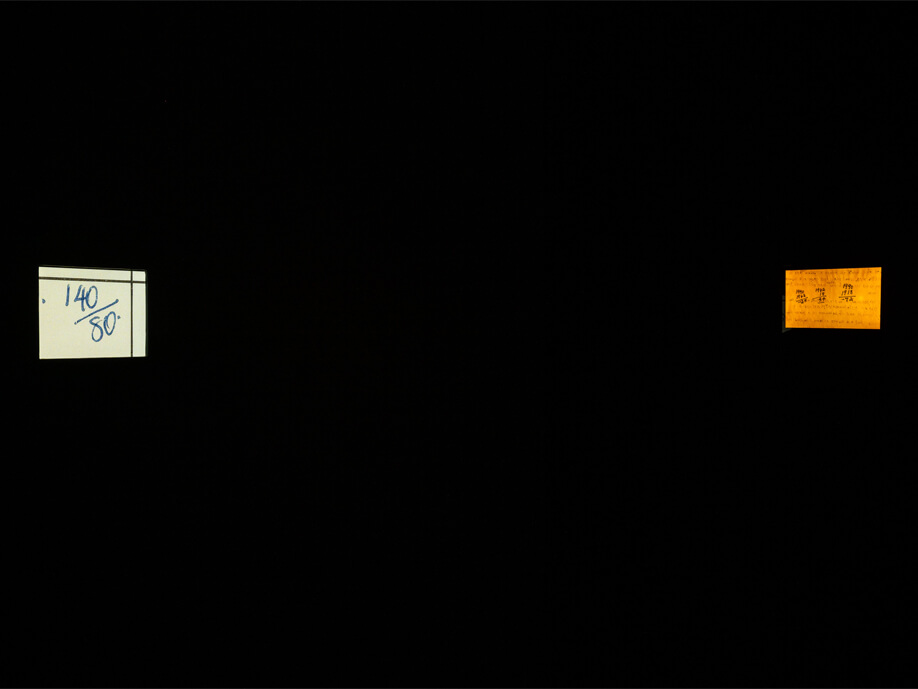

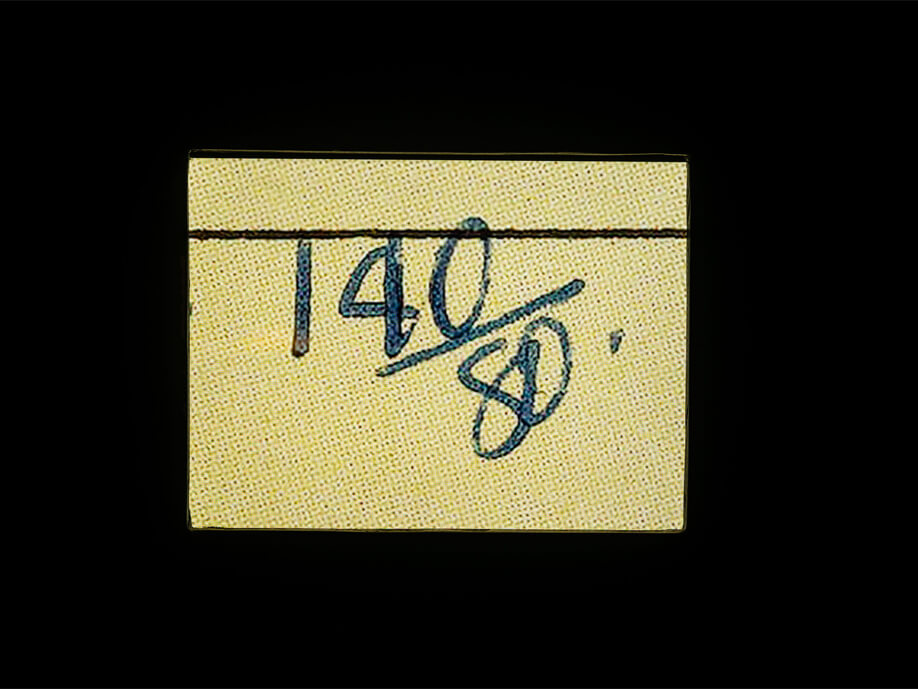

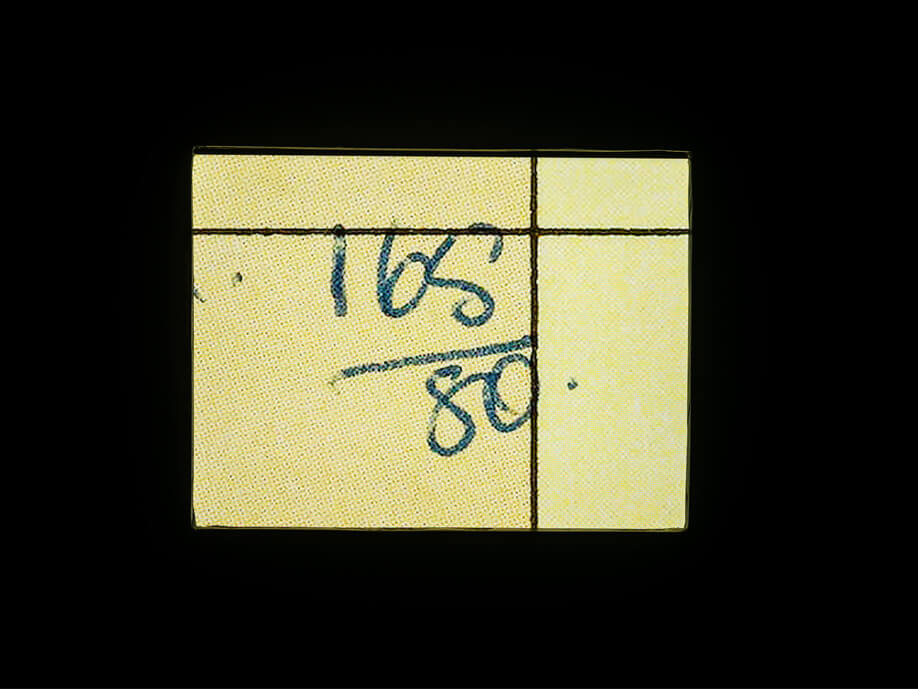

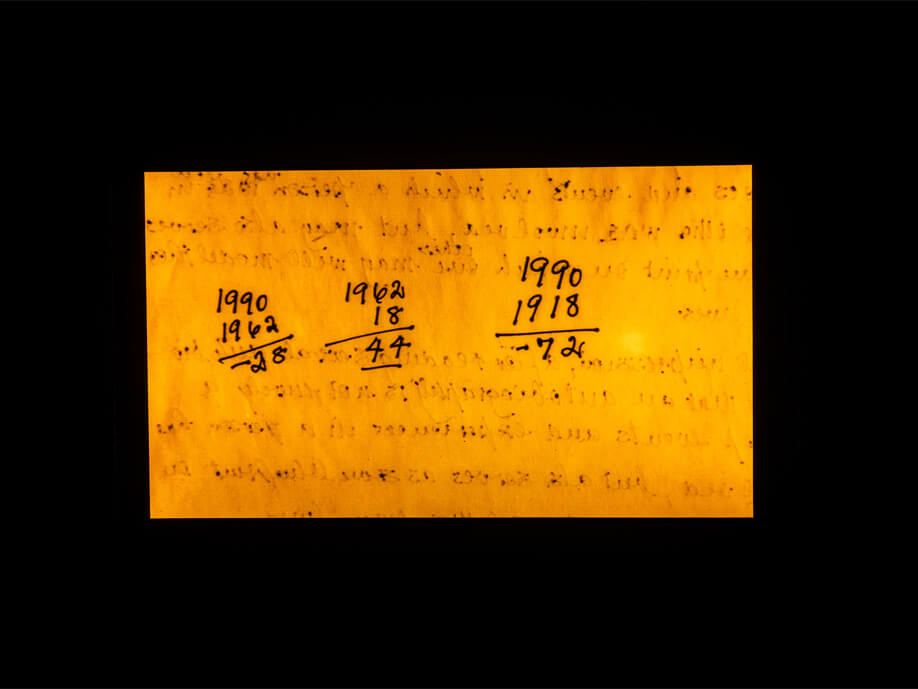

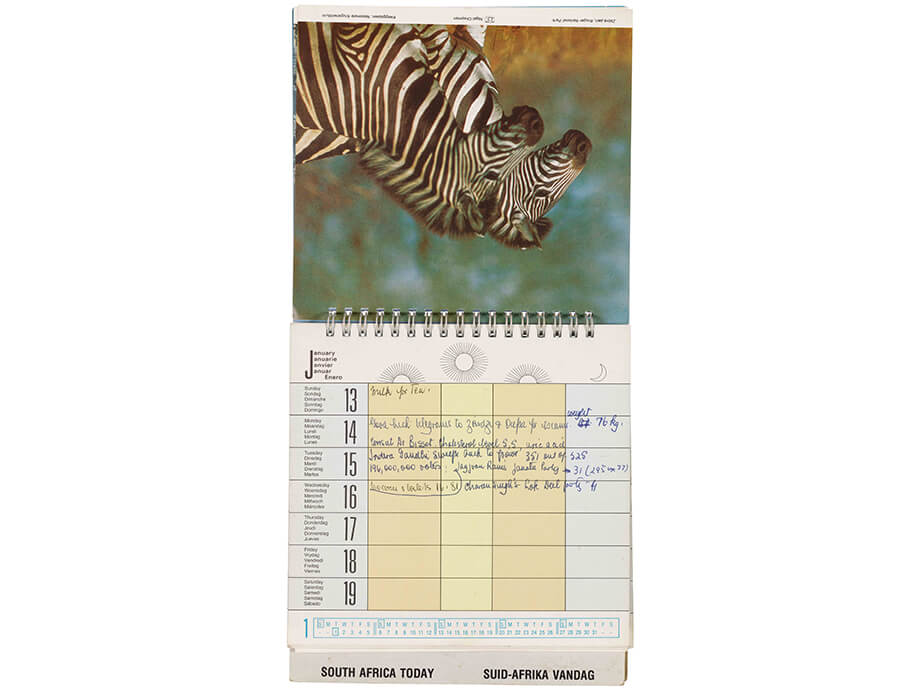

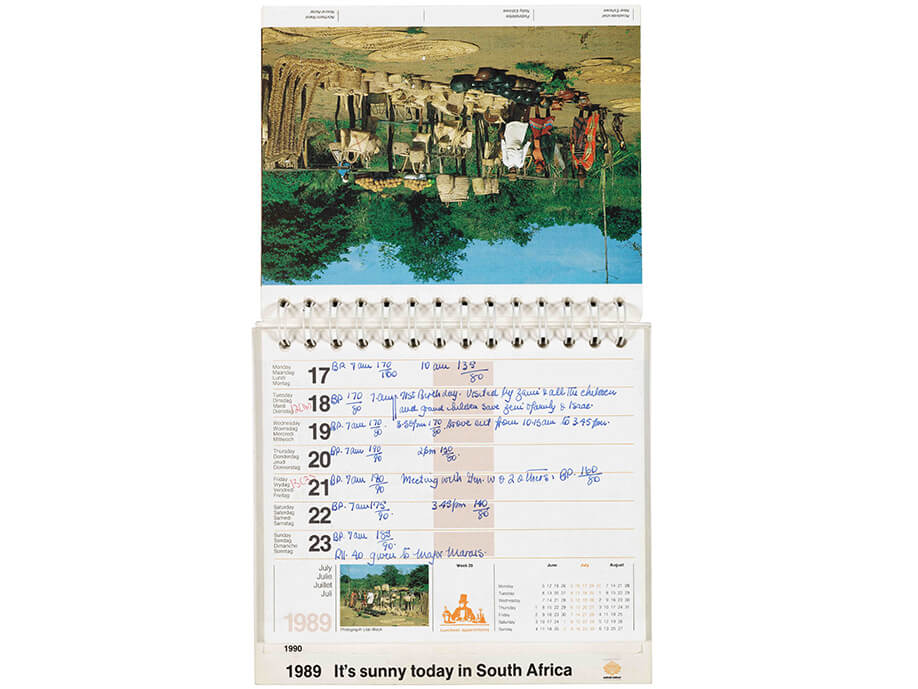

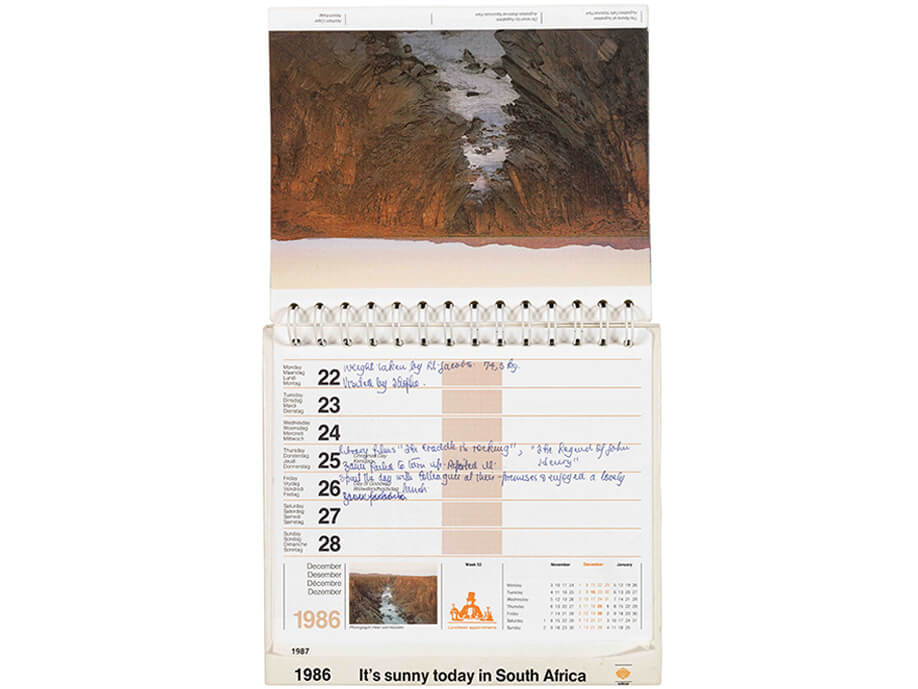

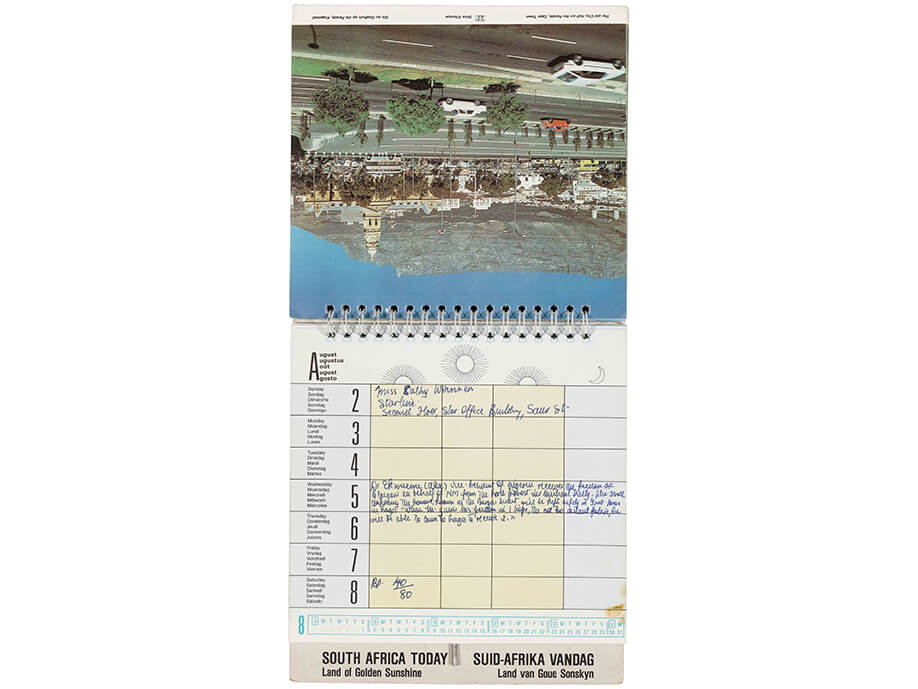

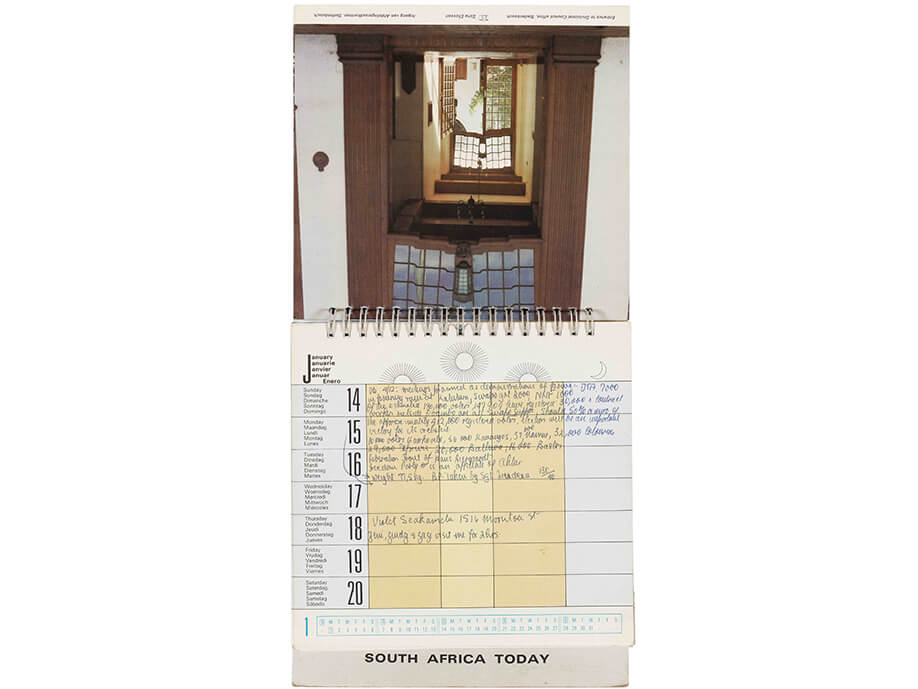

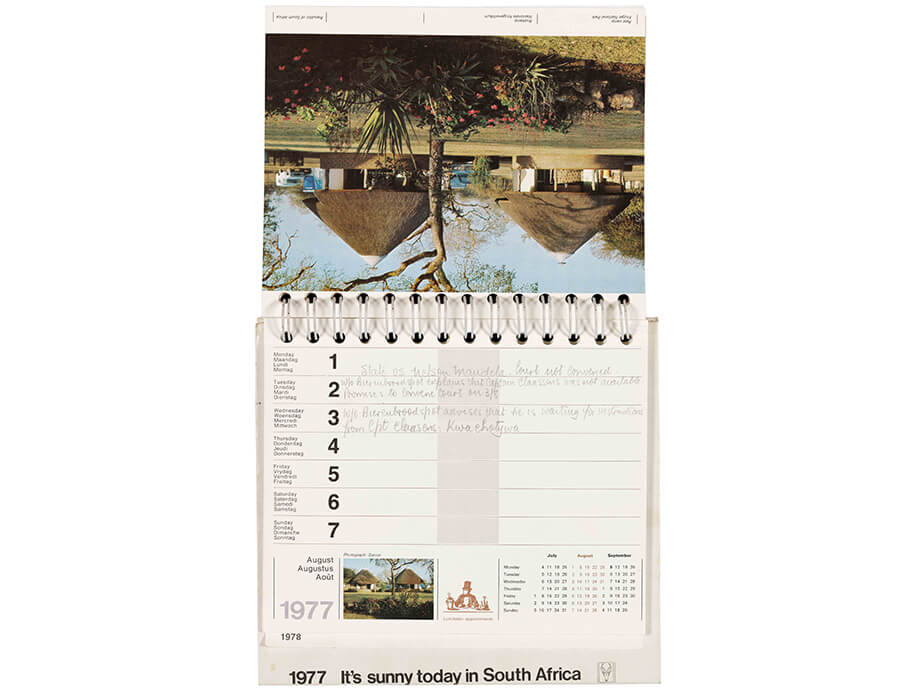

The installation includes a replica of a note with calculations by Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first black president, and a numerical autobiography that captures his complex life in stark figures. Each sum signifies key milestones: years in prison, his age at initial detention, and his age upon release. Alongside this arithmetic is a video of Mandela’s blood pressure readings, carefully noted in his prison calendars. These inscriptions denote cardiac time within the perpetual flow of calendar time. Additionally, the work highlights a recurring motif of the sun and moon in transition, forming cycles of days and nights visible across multiple pages of these calendars.